2026.02.03

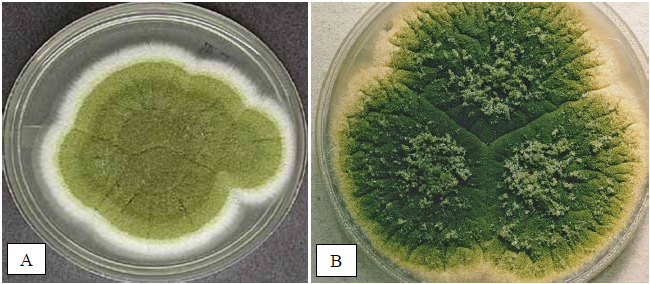

Aflatoxins are one of the most important mycotoxins, or fungal toxins, which contaminate food products and pose a threat to human and animal health. Due to the significance of this fungal toxin in the food industry and the need for better understanding of it, this article addresses the production of aflatoxins, the types of aflatoxins, foods susceptible to contamination with this fungal toxin, as well as their risks to humans and economic losses.

Aflatoxins and the Fungi That Produce Them

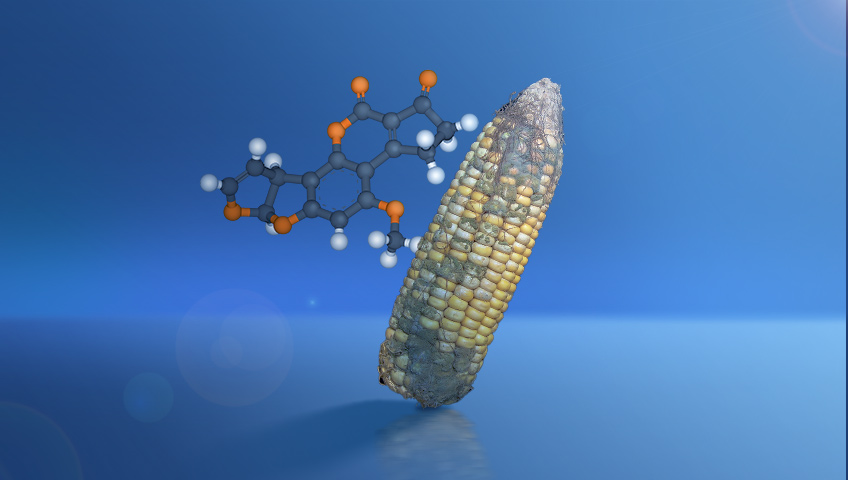

Aflatoxins are one of the most important fungal toxins, produced by approximately 24 species of Aspergillus fungi. The Aspergillus fungus was first named by an Italian priest and biologist because, under the microscope, it resembled an aspergillum a tool used to sprinkle holy water.

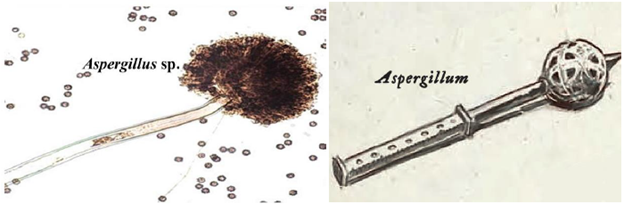

Aspergillus flavus and Aspergillus parasiticus are the most common fungi that produce the four main types of aflatoxins: B1, B2, G1, and G2. These fungi can be distinguished based on the color of their colonies. The colony of Aspergillus flavus appears yellowish-green or olive-green (Figure A), whereas the colony of Aspergillus parasiticus appears dark green (Figure B).

It appears that Aspergillus parasiticus is more adapted to the soil environment and is more prominent in peanut contamination, whereas Aspergillus flavus is more adapted to the aerial parts and is more prominent in the contamination of grains, tree nuts, and cotton seeds.

Agricultural products can be contaminated with Aspergillus fungi before and after harvest, as well as during storage and transportation. Sometimes, a product may become contaminated with the fungus in the field but show no signs of contamination until after transportation and storage, at which point contamination may emerge during the storage period.

Common Types of Aflatoxins in the Food Industry

Aflatoxins B1 and B2:

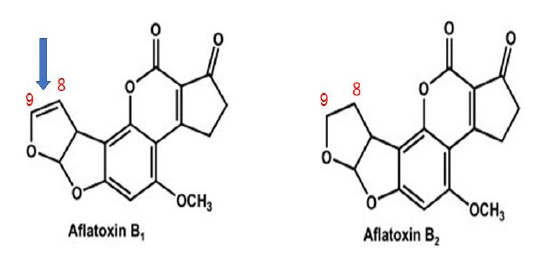

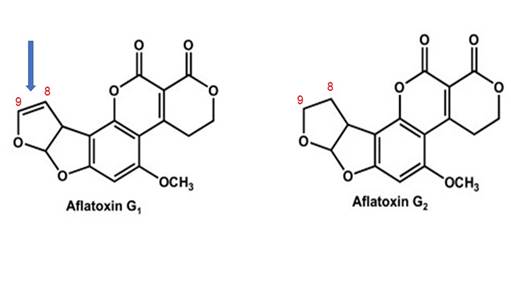

Aflatoxin B fluoresces under ultraviolet and blue light, which is why this aflatoxin is designated with the letter B. Structurally, aflatoxin B1 is similar to aflatoxin B2, with the difference that aflatoxin B1 has one additional double bond (between carbons 8 and 9). Aflatoxins B1 and B2 are produced by certain Aspergillus species, the most common of which are Aspergillus flavus and Aspergillus parasiticus. In addition, aflatoxin B2a also exists, which can be produced either directly by these fungi or as a derivative of aflatoxin B1. Aflatoxin B1 is the most common type of aflatoxin and is a thousand times more potent in carcinogenicity than benzo[a]pyrene.

Note: Benzo[a]pyrene is one of the most common and dangerous chemicals among polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. It is formed as a result of the incomplete combustion of coal, oil, gas, and other organic materials such as tobacco. During the preparation of certain foods, such as smoked rice, smoked fish, and grilled foods like kebabs, benzo[a]pyrene can deposit on these foods, and consuming them may increase the risk of developing cancer.

Aflatoxins G1 and G2:

Aflatoxin G fluoresces under ultraviolet and green light, which is why this aflatoxin is designated with the letter G. Structurally, aflatoxin G1 is similar to aflatoxin G2, with the difference that aflatoxin G1 has one additional double bond (between carbons 8 and 9). Aflatoxins G1 and G2 are produced by certain Aspergillus species, the most common of which is Aspergillus parasiticus.

It is generally accepted that Aspergillus flavus only produces aflatoxins B1 and B2 and does not have the ability to produce G1 and G2 aflatoxins. However, in 2019, strains of this fungus were discovered in Korea that could also produce G-type aflatoxins. In addition, aflatoxin G2a also exists, which can be produced either directly by Aspergillus flavus or as a derivative of aflatoxin G1.

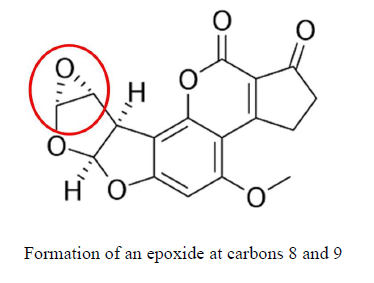

Aflatoxins B1 and G1 are more hazardous and toxic compared to B2 and G2 because B1 and G1 contain a double bond between carbons 8 and 9. This double bond allows the formation of aflatoxin epoxide (a triangular-shaped structure consisting of two carbon atoms and one oxygen atom) in the liver, which causes DNA mutations. Additionally, by binding to RNA and proteins, it inhibits protein synthesis, resulting in impaired cellular function. Therefore, aflatoxins B2 and G2, which lack the double bond between carbons 8 and 9, are considered less dangerous compared to B1 and G1.

Aflatoxins M1 and M2:

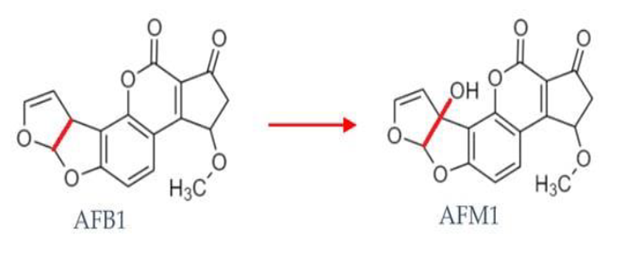

After consuming food contaminated with aflatoxins B1 and B2, aflatoxins M1 and M2 are produced through enzymatic activity, primarily in the liver, but also in other organs such as the kidneys, gastrointestinal tract, lungs and mouth. These aflatoxins have lower toxicity compared to aflatoxins B. Aflatoxin M is found in milk and dairy products. The European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) has estimated that the transfer rate of aflatoxins from cows to milk is on average 1–2%, while in high-yielding cows it can increase up to 6%.

Regarding contamination of products with fungal toxins, aflatoxins B and G have been reported in cereals, legumes, nuts, oilseeds, dried figs, dates, spices, and more. In addition, they have been found in commercial products such as peanut butter, edible oils, pasta, various teas and herbal infusions, dairy products, cosmetics, and medicinal plants.

Animal feed for livestock and poultry, including corn, barley, wheat, alfalfa, soy, cottonseed meal, canola, supplements, and more, as well as pet food and horse feed, can also be contaminated with aflatoxins. After consumption of contaminated feed by livestock and poultry, these toxins not only damage their bodies but also reduce milk and egg production. Aflatoxin M is detected in milk and dairy products.

Conditions for Aflatoxin Production on Food Products

Aflatoxin production depends on environmental conditions such as drought stress, temperature, damage to crops by plant diseases and insects, or agricultural activities during planting, cultivation, and harvesting in the field. In the post-harvest stage, it depends on factors such as unfavorable storage conditions, including high temperature or humidity, the presence of insects, and prolonged storage time. Aflatoxins are often produced under warm and dry weather conditions on crops growing in the field, and under warm and humid conditions after crop maturity. In other words, high temperatures and drought stress before crop flowering and high humidity and heavy rainfall during harvesting, are important factors in the occurrence of aflatoxin contamination.

The level of aflatoxin production on crops in the field increases under drought conditions because these conditions cause cracks on the outer skin and husk of agricultural products and damage them, creating favorable conditions for greater fungal penetration and increased aflatoxin production. The longer the products remain under these conditions, the higher the contamination with this fungal toxin. Furthermore, under drought stress, the level of phytoalexins which are defense compounds naturally present in plants that protect them against plant pathogens such as fungi decreases, making the conditions more favorable for fungal growth and aflatoxin production. Another point is that, according to research, the type of field soil can also influence aflatoxin contamination of agricultural products. Sandy soils have a lower water-holding capacity compared to other soils, which increases the likelihood of drought stress and, consequently, higher contamination of crops with fungal toxins.

Aspergillus flavus grows within a temperature range of approximately 12–48 °C, and the optimal temperature for the growth of this fungus is around 35 °C. Aspergillus parasiticus grows within a temperature range of approximately 12–42 °C, and the optimal temperature for its growth is around 33 °C. The ideal temperature for aflatoxin production is 25–35 °C, with the highest level of aflatoxin production occurring at 28–30 °C, because the expression of aflatoxin-producing genes is higher at these temperatures. At high temperatures, aflatoxin B is generally produced more than aflatoxin G, whereas at low temperatures, the production of aflatoxins B and G is equal. Research has shown that at temperatures below approximately 7 °C and above 40 °C, almost no aflatoxin is produced, and if any is produced, the amount is very low.

Aflatoxin production also depends on light conditions, in such a way that aflatoxins are produced more in darkness compared to light, and at low light intensity, aflatoxin production is higher.

Even the type and amount of fertilizer used in the field play a role in aflatoxin production. For example, in the case of organic fertilizers, which include plant, agricultural, and animal residues and serve as a carbon source, excessive use of these fertilizers affects the carbon-to-nitrogen ratio, creating conditions that favor fungal growth and aflatoxin production. Moreover, since these fertilizers contain plant residues, there is a possibility that they are contaminated with fungal spores, the fungus itself, or aflatoxins. In addition, because these fertilizers decompose quickly, they increase the soil surface temperature, further promoting fungal growth and aflatoxin production in the field.

It is noteworthy that, according to research on poultry manure, if this fertilizer is applied directly on the soil surface around plants, it increases aflatoxin contamination. For safer use, it is better to apply it inside fertilization channels, which reduces aflatoxin contamination.

Furthermore, the appropriate use of mineral fertilizers based on soil analysis is recommended. If soil nitrogen is lower than the appropriate level or the level recommended by soil analysis, the carbon-to-nitrogen ratio is disrupted, increasing aflatoxin contamination. On the other hand, excessive use of nitrogen-containing fertilizers makes plants more susceptible to diseases and pests, weakening the plant and creating conditions favorable for fungal and aflatoxin contamination. In addition, it can increase the levels of chemical elements in fertilizers and their toxicity in plants.

Therefore, it is recommended that both organic and mineral fertilizers be used in a way that neither harms plant growth nor promotes fungal growth and aflatoxin production.

The type of irrigation can also play a role in the level of aflatoxin contamination. According to research conducted on flood irrigation, surface drip irrigation, and subsurface drip irrigation, it was shown that in subsurface drip irrigation, the population of aflatoxin-producing fungi was lower compared to flood irrigation and surface drip irrigation, probably because the reduced surface soil moisture in this method decreased fungal contamination.

Damage to crops caused by agricultural operations (especially during harvesting) and the activity of insects and rodents in the field and storage can create small spaces on crops that allow fungal growth and aflatoxin production. In addition, insects can act as vectors and transfer contamination onto agricultural products.

Another point is that the presence of nutrients such as protein, starch, and sugars in agricultural products affects fungal growth and aflatoxin production. Fat is one of the most important factors for aflatoxin production, and multiple studies have shown that fat-rich food products are often contaminated with aflatoxin B1.

The optimal relative humidity for fungal growth and aflatoxin production, especially near harvest, during drying, and throughout storage, is above 85%, whereas at relative humidity below 70%, fungal growth and aflatoxin production either stop or occur at very low levels. Furthermore, aflatoxin production also depends on the moisture content of agricultural products, particularly under storage conditions. Therefore, to prevent fungal growth and aflatoxin production, attention must be paid to this moisture. For example, when storing grains such as corn, the moisture content of the kernels should be below 12–13%, for pistachios it should be less than 6%, for peanuts it should be less than 9%, and for hazelnuts it should be less than 6%, so that neither fungal growth nor aflatoxin production occurs.

In addition, attention must be paid to temperature and relative humidity during transportation and storage. For example, for grains, the temperature should be below 15 °C, and for nuts, between 0–10 °C, with relative humidity below 65%, because even if the moisture content of the products has reached a safe level, high relative humidity during transport and storage can cause the products to absorb moisture from the surrounding air until they reach equilibrium with the ambient humidity, which increases the product moisture and contamination. (Of course, if the relative humidity of the air is low, the storage temperature can be set slightly higher than these values).

After following the necessary measures to reduce aflatoxin contamination at the farm, transportation, and storage stages, attention must be paid to proper food packaging. Since fungi require oxygen for growth and aflatoxin production, the oxygen present in the packaging should be removed as much as possible during food packaging and replaced with carbon dioxide (CO₂), nitrogen (N₂), or a combination of these two gases, which is known as Modified Atmosphere Packaging (MAP). According to research, the higher the concentration of carbon dioxide in the packaging, the more effective it is in inhibiting aflatoxin production. In fact, packaging that uses carbon dioxide alone is more effective in controlling fungal and aflatoxin contamination compared to the use of a mixture of nitrogen and carbon dioxide, or nitrogen alone.

Furthermore, regarding the type of packaging material, food products in packaging with high oxygen permeability are more prone to aflatoxin contamination. For example, in a study on aflatoxin production in packaged peanuts, the results showed that the highest levels of aflatoxin contamination occurred in packaging made of low-density polyethylene (LDPE) and polypropylene, respectively.

To understand the significance of aflatoxin contamination in the food industry, it is important to consider its harmful effects on consumer health, the economic losses incurred by producers, the significant reduction in the trade of agricultural products from developing countries to developed countries, and the denial of entry permits for many shipments due to aflatoxin levels exceeding the allowed limits in global markets.

Risks of Aflatoxins on Humans

Over 4.5 million people in developing countries are at risk from aflatoxins through contaminated foods. The harmful effects of aflatoxins on humans start with severe food poisoning, with symptoms including loss of appetite, restlessness, and low-grade fever, and may then progress to symptoms such as vomiting, abdominal pain, hepatitis, liver and kidney failure, brain damage, and even death.

Moreover, long-term exposure of the body to aflatoxins can lead to various types of cancer (liver, breast, lung, gallbladder, esophagus) and in children can cause underweight and stunted growth. Asia and Africa are the continents most affected by aflatoxins. According to a report published by the International Agency for Research on Cancer, 500 million people in Asia and sub-Saharan Africa are exposed to levels of aflatoxins that increase mortality and disease. Between 4.28% and 6.2% of primary liver cancers (cancers originating from liver cells, distinguished from secondary liver cancers that originate elsewhere and spread to the liver) worldwide are due to exposure to aflatoxins.

Maximum Limits of Aflatoxins According to Iranian and European Standards

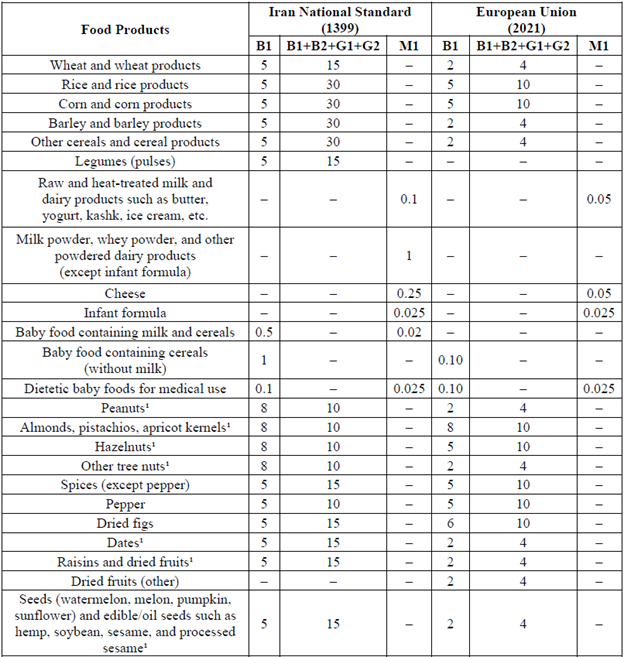

If contamination exceeds the maximum limits set by approved standards, agricultural products cannot enter domestic or international markets. The maximum limits of aflatoxins according to Iranian and European standards are presented in Table 1.

Table 1 – The permissible limits (expressed in ppb) according to the Iran National Standard and the European Union are as follows:

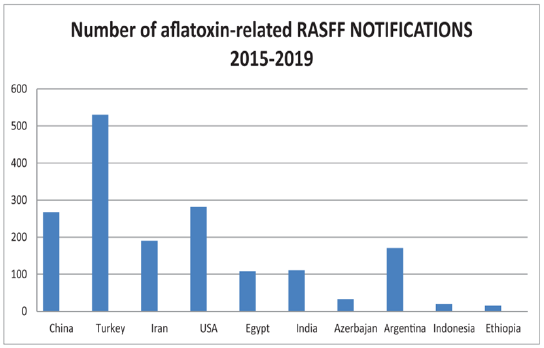

In the chart below, the number of aflatoxin-related alerts by the Rapid Alert System for Food and Feed (RASFF) in the 10 countries with the highest number of alerts is shown for the period 2015 to 2019. However, the production levels of the mentioned countries should be taken into account and compared as a percentage.

Finally, considering the risks of this fungal toxin and the contamination of a wide range of food products, as well as plant-based care and cosmetic products, and the occurrence of irreversible health hazards for humans, and on the other hand the economic losses due to returned export shipments, and given that even the use of existing industrial methods to reduce aflatoxin levels in agricultural products cannot reduce aflatoxin contamination by 100%, it is better, first, by being aware of the growth conditions of the fungus and aflatoxin production before and after harvest, to prevent the conditions necessary for the production of this fungal toxin, and second, for food producers to test the aflatoxin contamination levels of their products in food laboratories before entering the market, in order to prevent both adverse effects on public health and economic losses.